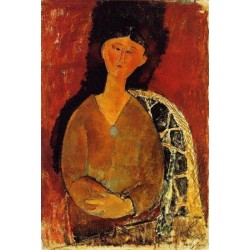

Amedeo Modigliani

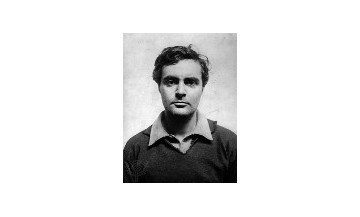

Amedeo Modigliani was an Italian-Jewish painter and sculptor and lived a life of excess. Addicted to alchohol, drugs and women, he died very poor and young in Paris in the year 1920, at the age of thirty five of tubercular meningitis.

Despite all of this, Modigliani’s output was considerable and his artwork is currently the subject of a blockbuster exhibition at Tate Modern, in London.

This major retrospective is actually the most comprehensive Amedeo Modigliani...

Amedeo Modigliani was an Italian-Jewish painter and sculptor and lived a life of excess. Addicted to alchohol, drugs and women, he died very poor and young in Paris in the year 1920, at the age of thirty five of tubercular meningitis.

Despite all of this, Modigliani’s output was considerable and his artwork is currently the subject of a blockbuster exhibition at Tate Modern, in London.

This major retrospective is actually the most comprehensive Amedeo Modigliani exhibition that was ever held in the United Kingdom. With over 100 artworks, it brings together a wide range of his portraits, landscapes, sculptures and twelve of his iconic, languorous, female nudes, some of which have never been shown in the the United Kingdom before.

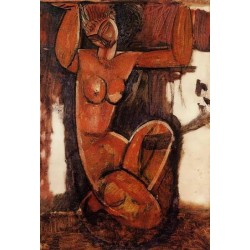

These very seductive figures, such as “Reclining Nude on a White Cushion” in 1917, “Female Nude” in 1916 and “Seated Nude” in 1916 constitute many of his very best-known atworks today. But in the early 20th century, these provocative paintings proved controversial, shocking the wole French establishment.

In 1917, they were included in Amedeo Modigliani’s solo exhibition in his lifetime, but were also subject to censorship on grounds of indecency: A police commissioner objected to Modigliani’s depiction of pubic hair, finding it very offensive.

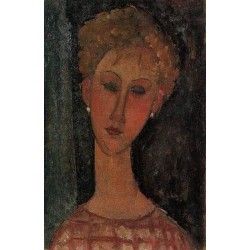

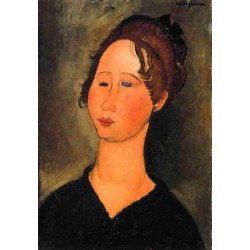

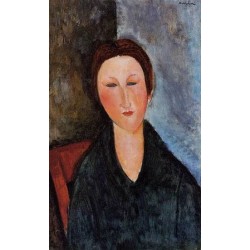

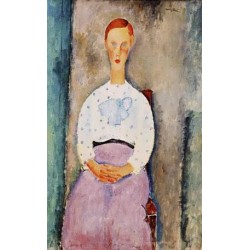

However, these artworks inclusion here is one of the exhibition’s highlights. The models appear very relaxed, their bold, curvaceous bodies and dark, almond shaped eyes gaze out with real coquettish confidence.

The sensuality of these model figures suggests changes in the lives of many young women, who then became increasingly independent. According to curator Nancy Ireson, women were of their moment in the 1910s, and their decision to pose was really based on economics. Models were actually paid five francs, says Ireson, which was approximately twice the average daily wage of a female factory worker during World War I.

He was born in 1884 in Livorno into a middle class Sephardic Jewish family, Amedeo Modigliani then moved to Paris in 1906 in order to develop his art career.

Bohemian, cosmopolitan Paris was the center of the art world and Amedeo Modigliani was actually “blown away by what he saw as generations colliding,” says Ireson.

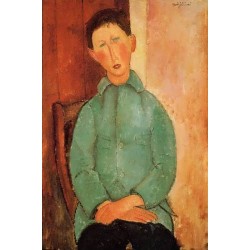

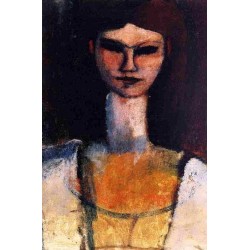

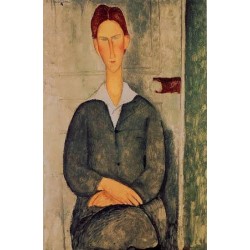

The city was a real place of excitement and offered new ideas and opinions that challenged him. He started to associate with poets, writers and musicians and soaked up the influence of artworks by other artists, such as the recently deceased Paul Cézanne, as well as contemporary artists including Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso.

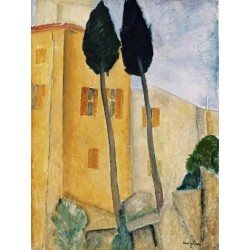

This then resulted in Amedeo Modigliani changing his traditional style paintings for broken brushwork and bright colors. “You cannot imagine what new kind themes I have thought up in violet, deep orange and ochre,” he then declared.

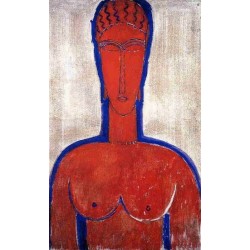

But Modigliani also had very strong ambitions to be a great sculptor, and one gallery was devoted to a display of his Heads, that was produced between 1911-1913. The shape of all these carvings reflects his interest in Egyptian, Cambodian and even African art.

On a visit one day to his studio, Amedeo Modigliani’s friend, the British sculptor Jacob Epstein, saw a few of his sculpted Heads and said that, “At night he would place a few candles on the top of each one and the effect was that of a primitive temple. A legend of the quarter said that Modigliani, had gone under the influence of hashish, embraced these sculptures.”

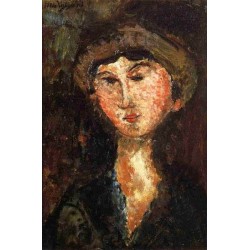

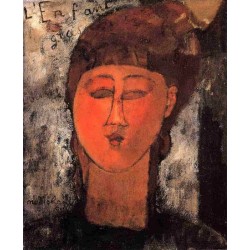

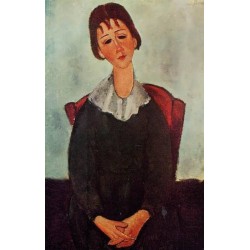

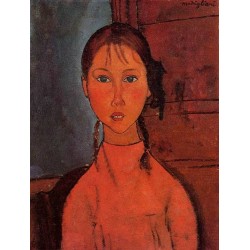

Although Modigliani’s aspirations as a great sculptor would be short lived due to a lack of funds and ill health — the dust from carving stones may have aggravated his breathing — his developing painting style of elegant, long necks, elongated, oval faces and almond eyes would then later feature in his paintings.

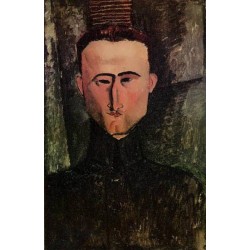

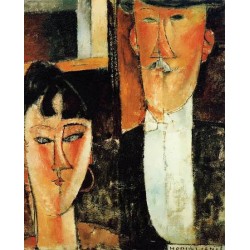

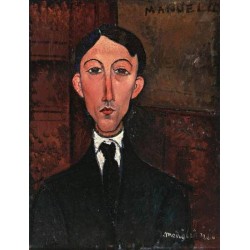

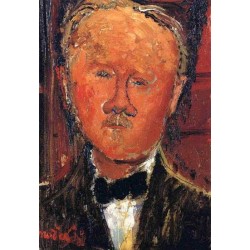

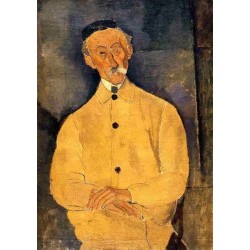

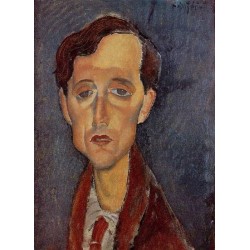

Amedeo Modigliani followed his foray into stone with portraiture and there are several rooms that are dedicated to pictures of his patrons and his friends, many of whom were other artists also living in Paris. These also included Juan Gris, Diego Rivera and Pablo Picasso as well as fellow Jews such as Moïse Kisling, Lithuanian cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and the great poet and painter Max Jacob, with whom Modigliani often discussed the subject of faith. Jacob has been the subject of a series of pictures and a graphite drawing of him, completed in the year 1915, shows Amedeo Modigliani’s handwritten inscription to his close friend who was also his “brother.”

Amedeo Modigliani was part of the Jewish artistic community, says co-curator Simonetta Fraquelli. “He was actually very proud of being Jewish and would not hide it.”

But Fraquelli was then quoted by the Jewish Chronicle as saying that Amedeo Modigliani was also a little different from his contemporaries, in that the first time he ever faced prejudice was in Paris — where many of the Jewish artists had left Eastern Europe for France due to anti-Semitism.

Amedeo Modigliani’s Jewishness is addressed in the exhibition as part of his special story without actually focusing exclusively on it, explains Ireson. The curators then chose not to explore Modigliani’s specific experience of anti-Semitism, says Ireson, having taken the view that a lot had already been written by academics on the subject.

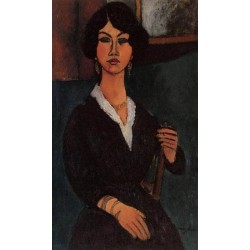

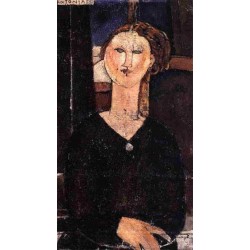

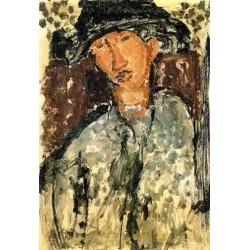

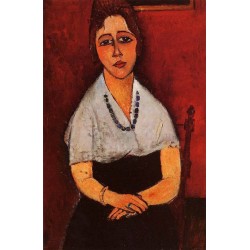

Although Modigliani had known many people, there are a few individuals who appear repeatedly in his artwork.

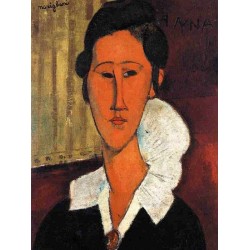

In his latter years, he turned to his close friends and his lovers as willing and convenient models. They included Modigliani’s art dealer and good friend, the Jewish poet and writer Léopold Zborowki, and Zborowki’s partner, Anna Sierzpowski, also known as Hanka.

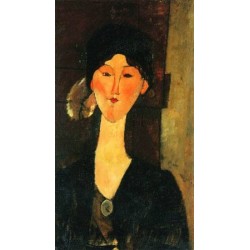

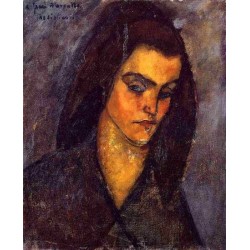

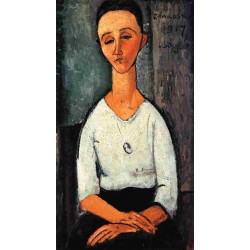

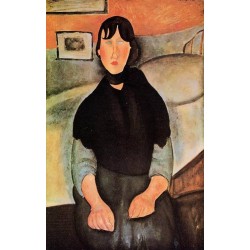

Despite him having had a succession of tempestuous relationships with many women, Jeanne Hébuterne became one of the most important people in his life. She became the mother of his child and Amedeo Modigliani’s most regular and favorite sitter — he painted her more than twenty times.

The couple met when she was a Nineteen-year-old art student and then moved in together, getting engaged against the wishes of her Roman Catholic parents. One of the last painting portraits of Jeanne (“Jeanne Hébuterne,” 1919), depicts her seated, one finger resting on her cheek with the rest of her hand curling, delicately, right under her chin.

Despite the extensiveness of the artworks that have been assembled in the exhibition, there is a lack of focus and also a frenetic quality about the show, mainly due to the inclusion of its countless and tonally similar painting portraits. There are actually some compelling pieces, but the excess of his artworks dilutes them — the sheer volume is very overwhelming.

Where the painting exhibition excels is in its integrated virtual reality experience, The Ochre Atelier. Through the use of a headset, all visitors can step into Amedeo Modigliani’s last studio in Paris. This used for the first time at Tate, this immersive, thrilling recreation also includes first person accounts by those who knew the artist.

The show’s highlights are very impressive, as are its ambition and its scale. Its overreach, however, is also its shortcoming. Most of the artwork does not match the artist’s penchant for reckless overindulgence, and lacks the sufficient drama and vibrancy to sustain an exhibition of this size.